We have crossed the border with Turkey a few days ago, are getting close to Greece and have thus left the multiple post-Soviet countries of Central-Asia and the Caucasus.

- First of all, read the posts from the last pasts months!

- Second, Central Asia is in Asia:

- China ∈ Asia

- Central Asia ∈ Asia

- ⊬ China = Central Asia

- Third, shame on you if you still do not know in which country Dushanbe, Bishkek or Tashkent are.

- Forth, even bigger shame if you cannot place Kazakhstan on a map (even worse if you have never heard of Baikonur and Gagarin!). (Cassie’s comment: can anyone tell that Cédric is a geography and history buff?)

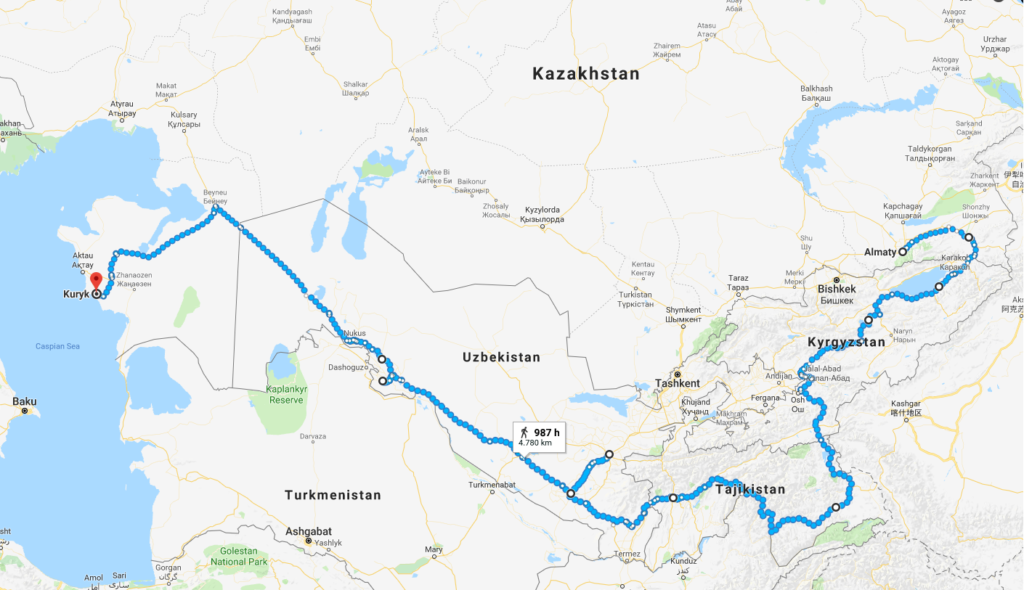

But just in case you are still lost with all the ‘Stans and the tiny countries of the Caucasus, here is our short summary of the last three months:

- Kazakhstan: by far the richest country of Central Asia, mostly due to a sparse population and a lot of natural resources, which helped to transition more quickly to a market economy.

- We liked:

- endless desert land areas, the steppe landscapes.

- surprisingly rugged mountains on the northern side of the Tian-Shan range, with canyons, glaciers, etc.

- little importance of religion, Kazakhstan also felt like the most social-liberal country of Central-Asia, with more diversity and fewer gender inequalities.

- The only country where you are likely to find better quality products (food or outdoor equipment), even non-fake goods!

- Almaty is surprisingly clean, well-maintained and even has bike-lanes!

- Good roads (and good enough drivers – although Kazakhs become slightly arrogant as soon as they are on the other side of their border)!

- We disliked:

- Kazakhstan also felt like the country with the most nonchalant people. It felt like whenever you ask something you annoy people – not just a random question in the street, but we also got refused from empty restaurants just because they were not motivated to cook today (seriously!), hotel owners annoyed that they have to go up the stairs to show the bedroom (checking the room before paying is a wise idea in any of those countries…), people who just tell you that they don’t know anything (although when it’s about their job), etc.

- For whatever reason, you can find more food products in Kazakhstan, but Kazakhstan was also the country where we found the ‘most-expired’ products. Shops have cans having shelf-life of several years, but still expired by 5 years! 10-year-old sardines are seriously disgusting (not sure if these were better at the beginning though).

- Distances! The country has many interesting sights, but those are usually in very remote areas, and very difficult to reach. Going from Almaty to Aktau will take you three full days in a train, with very not much in-between. And even in the Mangistau region (Aktau), you will need hours of driving (days of cycling) to reach some interesting areas.

- We liked:

After a few days on the road in Kazakhstan, we were getting a taste of the stunning landscapes to come

- Kyrgyzstan: a poorer country, yet more traditional and very much a mountainous version of nomadic Mongolia.

- We liked:

- Gorgeous landscapes, with changing views from valley to valley, the greenest country of all, with high-altitude steppes and plenty of horses.

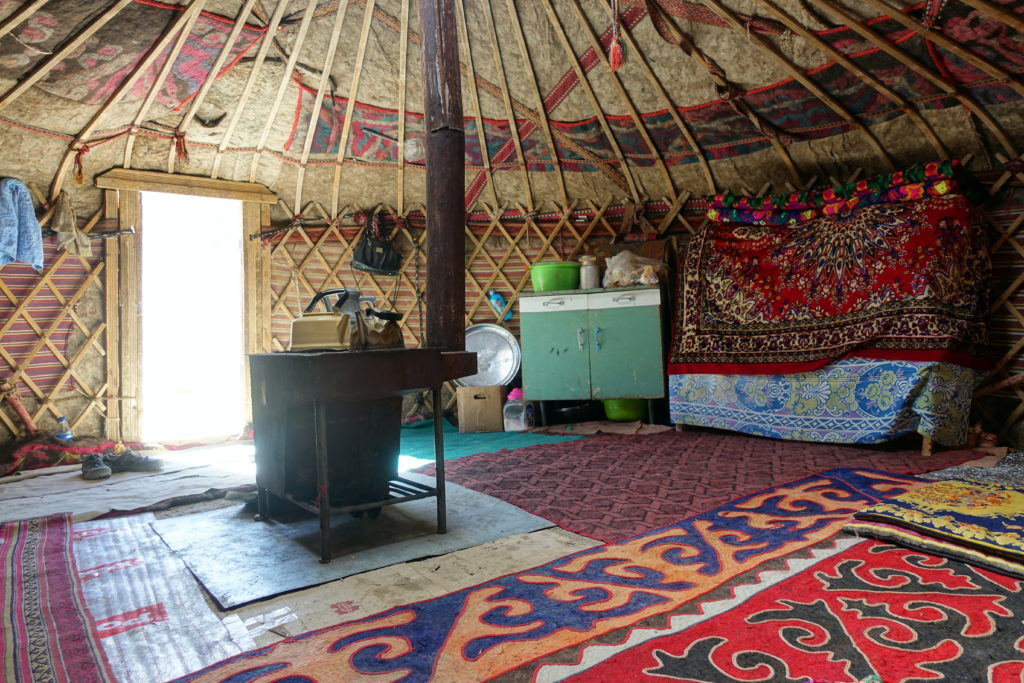

- The dream country for camping. Basically, any place in Kyrgyzstan is an awesome place to pitch your tent for the night. Locals do not mind, especially in the more mountainous regions, you have a tent, they have a bigger Yurt a few hundred meters away, everything is alright!

- Friendly folks in the mountainous regions, with a very relaxed atmosphere. Kids try to race you running next to the bike (even toddlers would kill many athletes at high altitude!) and adults wave at you without expecting you to give them money or buy a horse.

- Mobile internet is surprisingly good and cheap!

- Being able to go uphill faster than Kyrgyz Audi cars from the 80s. Audi is the cool car brand of the country, unfortunately a new Audi would cost a life-long wage, so they still spend a lot of money on rusty Audis, with still the driving style of a rally-championship. We got passed multiple times uphill by a roaring car, only to catch it up a few kilometers later with the driver randomly hitting the engine with a hammer.

- We disliked:

- The drivers! There is an obvious problem of alcoholism, with additionally some suicidal-driving behavior. Kyrgyzstan was the worst place to ride on roads, we always had to look at every single car coming from any direction – and get ready to pull-out the road at any time. They just don’t care! Luckily, we took some off-road tracks with very (very) little traffic.

- Tracks: because we did everything possible to avoid roads, and because there are really not that many roads, we ended up on the roughest tracks we have encountered this year. Kyrgyzstan was definitely the toughest country, both for the profile (continuously going up and down from 1000m to 3000m), and the road conditions (washboard, trenches on the road, rocks, etc.) – get ready to bike 7h for 40km and going uphill is not necessarily much slower than downhill.

- The Fergana valley, much more conservative, much more gender-divided, with men acting like young teenagers trying to show that they are stronger than you. Imagine a 12-year-old trying to look like a mobster, and you have about the idea of men in the Osh-Jalalabad region.

- We liked:

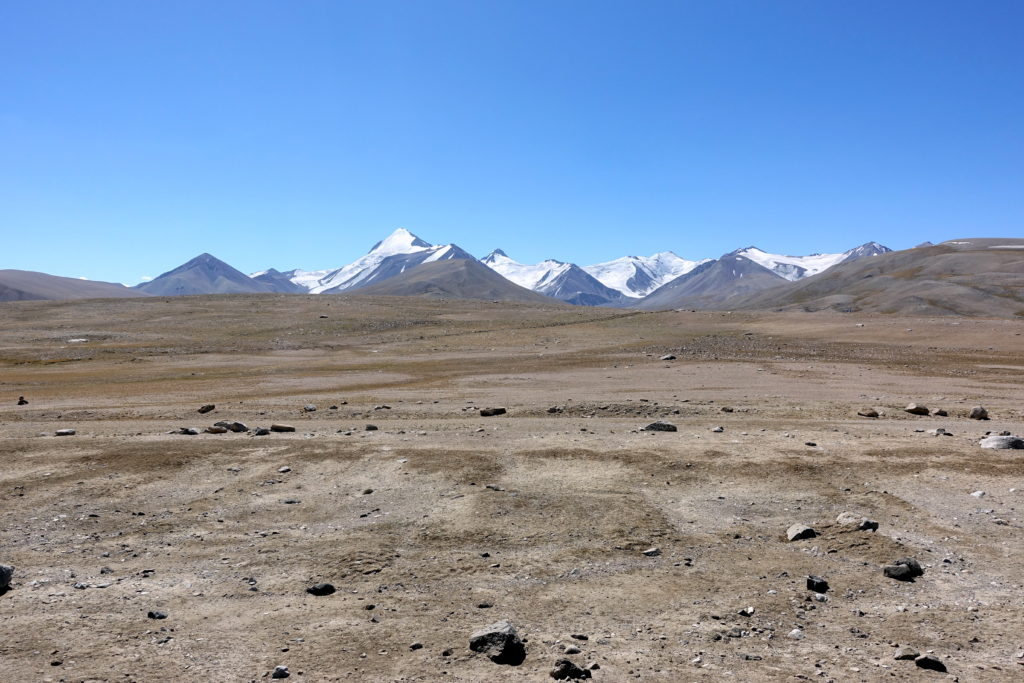

The Song Kul – Kazarman road: tough, but worth it for the views (the picture was not taken from a plane, but from the top of a mountain-pass)

- Tajikistan: the poorest of the Asian countries (except Yemen and Afghanistan, which are active war zones). The highest country on earth (average altitude), possibly one of the most remote and inaccessible regions on earth too. The feeling to be on a completely different universe.

- We liked:

- Cycling on another planet, over days we felt like doing some space travel between the Moon, Mars, Venus and other satellites of distant planets – lack of oxygen included.

- The road condition of the Pamir highway, although very rough, was easier than we had anticipated (also probably because after the tracks in the Kazarman and Song-Kul areas of Kyrgyzstan, everything seems easier).

- Incredible hospitality of locals in the Pamirs. People live in extreme poverty but are always happy to help, do not try to scam us, are very friendly, and amazingly many people speak English there. We really had the feeling in some villages to be with the toughest survivors, and the only way to survive is to help each other without condition or limit.

- Meeting a lot of other cyclists on the way, especially as we were cycling in the opposite direction as most of them (it is supposed to be easier to bike Dushanbe-Osh than the other way around).

- Dushanbe is a surprisingly enjoyable city. Not much to see, but it is a rare place to find good restaurants, it is relatively easy to get parts or gears, some parks and relatively clean.

- The Panj river valley is an indescribable feeling. You are cycling days looking at a medieval and almost mythical Afghan society. Afghanistan feels like being back in time several centuries ago, although it is interesting that even remote Afghanistan villages now have access to mobile internet. By the way, yes there has been an attack in southern Tajikistan – and apparently tourists have all left the area, which felt silly! Tajikistan is safe, and has now been downgraded by the western foreign ministries to the security level of western Europe…

- We disliked:

- Well, it’s hard to not get some type of sickness (mostly digestive) in Tajikistan! Electricity is far from reaching every village, running water is a luxury, and simply the remoteness does not help having a good food-hygiene. Most of the guesthouses are nevertheless clean and we did not get anything too serious. Plus, there is really no problem doing an emergency stop anywhere on the road when you only see 10 cars per day…

- Politics in the Dushanbe region is really “special”. There is clearly no democracy in Tajikistan, but our conversations – several people were trying to practice their English – were severely bridled. Dushanbe inhabitants are clearly privileged in the country, and they seem to all strongly and blindly support their president, including the fact that he should stay there forever, with his son taking-over later. Western countries, with elections every few years thus cannot be good… The area around Dushanbe felt like the most indoctrinated in Central Asia with an idealization of the leader everywhere. Discussions were surprisingly more difficult in the capital than in the rest of the country. The opinion of that leader is indeed very different in other parts (especially the Pamirs) of the country.

- Cycling several weeks around 4000m is physically hard. We both lost a lot of weight (it’s all gained back, don’t worry), you finish exhausted every single day, and after 1000km of continuous dirt roads (including Kyrgyzstan), we were just dreaming of asphalt.

- We liked:

- Uzbekistan: the most historical country, with old cities, many monuments and the core of the silk-road cities in Central Asia. Uzbeks thus consider themselves a little as being the only urban civilization (versus nomadic tribes) in the mountains or in Kazakhstan. Although very isolated (a double landlocked country, today far from any trade route, and yet with little interest to develop connections with neighboring countries) but nevertheless the most populated, Uzbeks consider unconsciously that all Central Asia shall be theirs.

- We liked:

- The road conditions are good! Especially after Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, we were glad to finally have continuous stretches of asphalt without too many potholes (small potholes are useful when cycling as they make car drivers a lot more cautious).

- The historic cities – basically Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva – are impressive and remarkable, they are well maintained and are worth visiting.

- Some generous people, particularly after near the Tajik border until Qarshi (very few tourists) – we had everyday people offering us chocolate bars, ice-creams, and other treats!

- The new president seemed to shake things up in the country and finally try to solve the serious problems of the country (since 2016), this is particularly notable after the reign of the previous dictator Karimov (completely nuts): tourism develops, Uzbekistan opened its border more widely to its neighboring countries, they finally want to get rid of the cotton industry and the corruption linked to its system, possibly work on refilling the Aral Sea (that may take a few decades!), etc.

- We disliked:

- Some men are slightly creepy! Every single women tourist that we have met (not those in guided tours!) have encounters some type of weird moment – from men who want to kiss you, to some touching or grabbing, etc. There is some impunity against forced marriage (including children), and women are clearly a lower social class. It did not feel like something directly liked to religion (few Uzbeks are practicing, women do not wear veils or hide and are active in the society), but a deep cultural habit.

- Again, about men (who are the primary car drivers) … we got used to honking and so on, but some Uzbeks felt like being really pushing it. It is not just a short honk and waving, but a non-stop honking behind you, at your pace, until you acknowledge them. We are all day long on the road, and that would be fine in the Pamirs with 10 cars per day, but Uzbekistan has a larger population (with a lot of cars) so we got slightly tired of getting interested in every single driver. Even better, you get regularly stopped (the car passes you, puts the warning lights on and slows down until you stop) by group of guys who want to take a selfie with your own camera. It’s funny once, but we have a lot of pictures of Cedric (Cassie is happy to be ignored) with a group of locals on the side of the road… The real treat was having a driver slow down and take a video of us on their smartphone while still driving – funny at first, but we don’t condone distracted driving practices (and mostly stopped the bike when we saw what the driver was doing, so they would be forced to drive ahead).

- The desert landscape! The country west of Bukhara, and especially after Khiva, is desperately monotonous and boring. I really would not recommend anyone to cycle across that (we only met one person, a Swiss, who had done it, and he told us he became almost insane after the several weeks alone with the exact same sight).

- The Plov! I guess this can be about Central Asia in general, if you look up the region’s national dishes, but Uzbekistan is richer, and they have enough farmland to grow other things than cotton – and then possibly make some recipe variations! Seriously, why does everyone revere this dish? It feels that they only like that, only serve that, and make that and almost worship it. It is not intrinsically bad, but we just could not see it any longer. Cassie was also starting to loathe the mutton sitting on top of the dish.

- Uzbekistan is the country where we got the sickest (again, digestion issues). We however cannot explain it there by the lack of electricity and fridges.

- We liked:

The next morning, we awoke to cold and windy weather (despite the near-cloudless skies) and had a little pep-talk for the Kyzyl-Art pass. This next pass surpassed the Taldyk pass by a few hundred meters – looming over us at 4250m and would test our ability to acclimate to the high altitudes. A few days prior, Cédric and I started taking Diamox to ward off any altitude sickness – something we don’t want to encounter while on our journey. Cycling the Pamir Highway is supposed to be easier in the opposite direction that we are taking, as starting in Osh means going from 900m to 4300m in only 4 days. We are cycling towards Europe, so well, we’ll cycle the road the hard way! However, the ascent between our campsite and the pass was still significant to make us catch our breath. Once we reached the final switchbacks leading to the top, Cédric and I needed to get off and push the bike, because the road quality deteriorated along with the amount of oxygen. Every few tens of meters up, we needed to stop and gasp for air for at least 30 seconds. Finally, after what seemed like forever, but probably maximum 15 minutes, we made it to the top and celebrated, ignoring the cold and strong winds for just a few seconds.

When we were done rejoicing, we hopped on the tandem and slowly made our way down to the Tajik border just a kilometer down from the pass. At this border control, things were a bit different – no electricity and internet connection required everything to be entered by hand and checked a few times by various guards. The longer process also allowed us to watch the various types of travelers pass through the border; some were locals visiting family, others were sand-blasted tourists like ourselves, either cyclo-touring or participating in the Mongol Rally (link). The ones who stuck out were a Swiss couple who drove up and inadvertently sprayed everyone in dust with their enormous MAN Action Mobil Global (link). (As a side note, we give heavy eyerolls when we see these types of overlanders/unimogs, which has been in Central America, Africa, and here. These vehicles must be one of the most culturally insensitive things we’ve seen while traveling. It takes up the whole road and gives the impression that the local hotel [or any interaction with the locals besides at the gas station] is too treacherous… Really, there’s no reason to drive around a 600,000EUR moon rover to go down the same roads we cycle on. People are well aware of the price of those shiny luxury trucks – just imagine that a truck costs as much as the annual income of 3000 people…

Munching on some gifted dried mulberries (thanks dude in the KZ car!) while waiting for passport checks

Just before leaving, we also encountered a group of chauffeured British cyclists who treated us like a human zoo – far enough away to not need to talk to us, they were happy snapping pictures of us without asking. Once again, the behavior of people traveling in organized-groups is a desperation – yes, we have a special bicycle and yes, some people want to take pictures, but even locals in Central Asia with whom we do not share a common language ask first and we are always happy to even put the bike on the kick-stand. But when western tourists (and even worse for native-English speakers) hide behind a fence to take a picture – that they are never going to look at ever again back home – it’s just a feeling of hopelessness… (/rant)

Although the previous night was spent in No Man’s Land, the landscape just after the Tajik border felt more like No Man’s Land- from green mountains on the Kyrgyz side, we descended to a moon-like landscape with no vegetation in sight. The mountains grey and the water salty. Continuing on, we descended into Karakul looking for a homestay for the night. Once we got over the second ‘pass’ of the day, we were greeted with stunning views of Lake Karakul and the glacial mountains surrounding the plains. At our homestay, we were happy to be welcomed with a pot of tea (at the end of the day, all worries about water-related illnesses and low boiling temperatures faded away – for better or worse). We also shared dinner with some other Americans, one who grew up mere miles from my Dad’s childhood home.

The next morning, we ate breakfast and got ready for the journey towards the Ak-Baital pass, the highest point of our trip. Before we left the village, we managed to trade SIM cards with passing cyclists headed towards Kyrgyzstan and gathered bread and water for the ride. The landscapes remained barren and mountainous, and we wondered how anyone decided to live up here, let alone stay here over the winter. As we got closer to our planned campsite, the paved road gave way to rough washboard and we were instantly reminded of riding the Kazarman road in a week ago. Shortly before we wanted to call it quits for the day, we spotted a yurt stay and decided to stop for tea before setting up camp, and escape from the wind. As we’ve now learned, asking for a ‘chai’ also implies bread and other homemade treats, like yogurt and butter (and no refrigerator in sight, so we’ve really thrown all caution to the wind at this point). After our snack and few kilometers down the road from the yurt-stay, we found a place among the marmots that seemed slightly less windy than the rest of the valley, although Cedric spent an hour in the tent reading while holding the tent wall – luckily the wind always calms down in the evenings.

Waking up from a chilly night, Cédric and I packed our things and set off for the pass at 4655 meters. Within the first few kilometers, we stopped several times to chat with other cyclo-tourists coming the other way, having just conquered the pass. We shared tips about the days ahead and gave each other words of encouragement for the upcoming stretch of road. As we continued our ascent, we found even more marmots scurrying across the road and a local family, herding goats through the valley. Finally, without pushing this time, we made it to the pass – which was slightly underwhelming for such a feat. After a few fits of coughing and pictures from the area, we cycled down the valley and were greeted with new red and yellow landscapes. As the day progressed towards Murghab, our tailwinds from the past few days gave way to strong headwinds and the last bit into town was almost unbearable. We were supposed to be going downhill, but our speed would have said otherwise. In the evening, we shared a guesthouse with a few like-minded travelers and experienced our first bucket shower of the trip (no indoor plumbing has some neat alternatives). We will be staying in Murghab two nights with the plan to do absolutely nothing the next day, only rest and drink some chai, with a view over the Chinese side of the Pamir and the Muztagh Ata in the background.

]]>

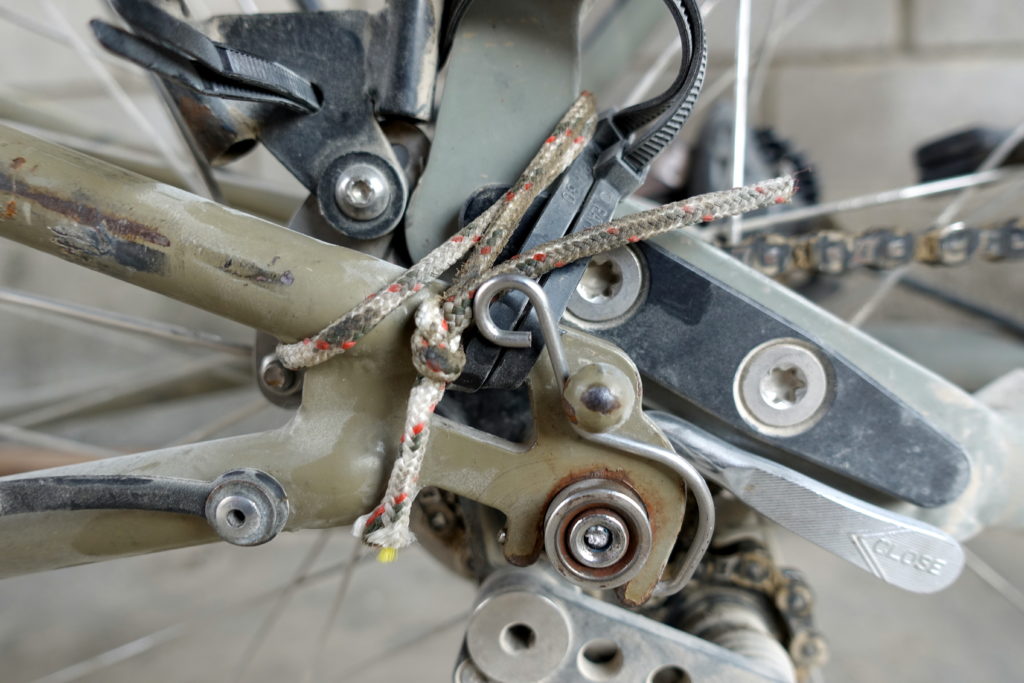

If you need any part, you can probably find it… although it won’t come in shiny new packaging! It may also be second-hand (or fifth-hand!), probably a chinese knock-off and if you have any special part – well, be inventive!

As we were packing up to leave, we noticed that a piece of our trailer flag was missing. Although the merchants were trying to tell us that we had no flag when coming, we were sure about the opposite (simply because we had a part of the flag remaining). We looked around for a couple of minutes just in case we would have put it inadvertently somewhere, but nothing. A little pissed off that someone would have taken such a useless and ridiculous part (a glass-fiber stick holding a yellow flag), yet fairly useful (we try to believe that cars notice the flag when stopping behind us instead of running into us). We walk away in a bad mood, when Cédric sees a kid holding a part that looks very much like ours, grab it from the kid and (try to) explain to the dad (and a policeman who was drinking a tea, probably as his main job task) that his son is a thief… unfortunately our Russian language skills are not fluent enough to explain him that “qui vole un oeuf vole un boeuf” (give him an inch and he’ll take a mile), and that they should consider doing something. We got a lame explanation that actually an older person took it and gave it to him as a gift, the policeman just enjoyed looking at the scene with his tea – we took the part and left, not thrilled and again not excited about the Fergana valley (Kyrgyzstan is composed of several ethnic groups in the different regions of the country, the Fergana valley is far away from the nomadic way of life in the mountainous parts of the country).

Exhausted from the day’s events, we ventured out once more to find a late lunch, an Orthodox church, and yet another Lenin statue. Later that night, we once again left our guesthouse for shawarma and roam around the streets. Cédric, looking like a knowledgeable tourist, was approached several times by other travelers looking for a place to stay or a map of a city. We also had a bizarre exchange with a couple who wittingly left their cellphones at home because who needs a phone anyway, explaining us that all hotels are booked-out, only to use our phone as a map and to find them a hotel for the night (where not a single place was sold-out, but apparently a couple of dollars were still too much – some tourists are seriously dumb). The next day, we rested and prepared for the onward journey towards Tajikistan, happy to leave the mess of the city and back to quiet camping spots.

Kyrgyzstan is mostly muslim, but the slavic influence from the USSR remains, and a community of orthodox christians live in the larger cities. We got confused a few times between them (looking Caucasians) and tourists (mostly westerners)…

Another Lenin! This time well maintained and extra-large. It’s more and more difficult to find those statues, the USSR has not always been the greatest for local culture.

One of the oldest mosques in the city with Mt. Sulayman-Too, although we were too tired/lazy to do the ~20 minute climb up

We found that the Kyrgyz tend to go all out for celebrations. It wasn’t long enough, so they also increased the height.

We left Osh the next morning and maneuvered the traffic as we cycled south. Just a few kilometers outside of the city, we were passed by a few mountain bikers with suspiciously clean and fancy mountain bikes, not a single scratch, then a few more, and at lunch, even more. At one point, we spoke with one of them and found out that they were part of an organized tour that was chauffeuring their luggage from hotel to hotel as they made their way across the Pamir Highway. As usual, most of the people of that group did not say hello (while 100% of cyclo-tourist do), and one explained us that unlike our tour, their 10-days circuit was more adventurous! Sure! Well, the joke was that we had a similar pace for the next three days (no idea which road they took afterwards, but we suspect some bus-ride cheating), although the iron horse is about 70kg heavier, without a mechanic, someone to prepare meals and accommodation, and the backup backseat of a SUV. For Cédric and me, this type of luxury bike trip doesn’t test your true grit while on the road, and group-tours are definitely never going to be an option anytime soon (we will have another similar encounter with an uninteresting, shinny but unfit and rude British group a few days later…next post!).

As we continued our day climbing up towards the Chirchik pass, we met two New Zealanders and an Italian guy who were also making their way towards the Pamirs. Just before we reached the pass, the storm clouds that had been swirling around the mountains the whole day broke and we sought shelter in a kumis stand on the side of the road. As I saw the smoked leather bag where kumis originates, I thought to myself, ‘Never again.’ The rain shower was quick, so Cédric and I hopped back on the bike and found a camping spot near a river just a few kilometers after the pass. We were met by the other cyclists and ended our night with a campfire while telling stories of our travels on the bike.

Unexpected gifts from the owner of our guesthouse. We could neither find an excuse to refuse it, nor give it to someone else, so we’ve carrying a not-so-useful hat all around the Pamirs in our bag…

Now he’ll definitely fit in with the Kyrgyz men (he just needs to improve drastically his vodka consumption – we swear, not a single drop since we arrived in Central Asia!)

A common sight while cycling through towns and villages. A kid with a bike sees you, forces to pass you and stops 50m afterwards – faster than the two foreigners: mission accomplished!

And we always attract a crowd. This time three (!) buses of German students at the pass, one of their bus had destroyed a wheel, and we ended up been as fast as they were the next three days.

Keen to make good gains on our way to Sary Tash, we set off the next morning for the last downhill ride of our day. The further we cycled, the more varied the landscapes became – red canyons and glacier studded mountains way in the distance. Along the way, we were greeted by cyclists who were coming off of their Pamir high and excited by the prospect of completing their journey and possibly a proper city with running water. At lunch time, Daniele, the Italian cyclist, caught up with us and we continued cycling up the valley and through small villages. Here, children are used to cyclists and seemed to have a sixth-sense for when one was approaching- eager to run out to the street screaming ‘Hello!’ and sticking their hand our for high-fives. In the evening, we found the local watering hole near the village Kichi-Karakol with pure water coming from higher glaciers and decided to camp near the fresh water, despite the amount of people coming and going. In our journey towards Sary Tash, it became increasingly apparent how many villages and towns in Kyrgyzstan don’t have basic indoor plumbing. We (Cédric more than I) became used to outhouses, but along this valley we saw an increasing amount of people using wells and pumps for water which are located on the main road. In some villages, such as Kichi-Karakol, the preferred water source was a nearby stream coming directly from the mountains (protip: don’t take water from the main stream). As we set up our tents, family trucks and cars passed to fill up large drums with fresh water. Daniele also entertained two teenagers by allowing them to ride his bicycle and took pictures of them with their smartphones proudly sitting atop his bike– and after a couple of minutes wondering if letting a 10-year-old ride his bike across the river was such a smart decision.

Tearing down camp in the morning. Central Asia is more remote than any of the previous places we had been too – except for the amount of cyclists: we have often met more people some days than in 10 weeks across Australia!

We’ve been passed by a lot trucks carrying an impossible amount of hay (yes, there is a truck under that pony’s dream)

The next day, we continued our slow climb up towards the Taldyk (Thankful in English) pass. We crossed the last few villages, giving more high-fives to the children, and waving to the locals. As the valley began to narrow it also became steeper and finally as we neared the end of the valley, we started the arduous switchback climb up 1200 meters. Each time Cédric and I stopped, we were panting because the air was thinning. As we reached the top of the Taldyk pass at 3650 meters, we recorded a new altitude record for the Pino. We took pictures with Daniele and then continued cycling to Sary Tash. As we descended into the Alai Valley, we could see the glacier-covered peaks of the Pamir Mountains at over 7000 meters, with the Lenin Peak becoming more and more visible. While buying supplies at a market in Sary Tash, Cédric met two tandem+trailer cyclists from France who invited us to stay at their guesthouse for the night. As we arrived, we were surprised to see even more cyclists and we were all excited to share stories of our journeys over tea and a heaping plate of potatoes. (From here on out, Cédric and I will be attempting to avoid meat due to lack of constant electricity – generators for a few hours at night – and clean water sources… we’ll let you know if we succeeded).

Osh to the Tadjik border is basically a long 200km+ continuous climb starting at an altitude of 900m up to 4300m.

We have no idea what this arch is for… we suppose it’s the gateway to the Pamirs? Or maybe a temporal gate, had the Soviet union found time-travel? We did not get into Moscow, so it probably does not work anymore…

Karl Marx’s style in the foreground, peak Lenin in the background (the white mountain in the middle is not a cloud, but a 7000m summit!).

The main road going through Kazarman. You may encounter about as many drunkards as cars (with possibly a drunk driver in it) on it.

Dinner in Kazarman. A really weird grandiose restaurant with private dining rooms and huge tables for tens of guests – but we were the absolutely only customers that evening.

How we’re holding everything together (the zip-ties and cord held, not the metal reinforcement-repair that broke after 50km of washboard path. The screw-head in the middle lower part of the picture broke – very stupid – this is however what maintains the trailer on the bike – so actually pretty serious.

After another night’s rest at our guesthouse, Cédric and I set off for the mountains. Just as we were making our way out of the city that Sunday morning (and warding off two dogs with a handful of rocks), we heard a loud engine revving behind us. Slightly confused by the sight unfolding a few hundred meters behind us, we watched a way-too-many-decades-old Lada (a soviet/Russian brand of car) reach a top speed, attempt to make a sharp turn, then doors flying open as it crashed into a 3m ditch. Stunned, we watched a man stagger out and realized that there had been a drunk driver at the wheel – this was our sign to get the hell out of town before anything else happened. Just as we were making our way up the first hill out of the city, the weather quickly deteriorated, and we were caught in a shower. Continuing, we slowly rolled through Kekerim and attracted the attention of nearly every dog in the village, so Cédric was happy to continue practicing his stone throwing (with a much better result: 2 hits! Local dogs are much bigger though!). As the day went on, storms and showers rolled over us and we were happy to find a spot to camp near a river. Here, as we were warned by passing cyclists, there would be a lot of curious children to watch us set up our camp for the night. Just as we made our way down to the river, the kids from the nearby yurts made a human roadblock and showed us the way to the designated camping spot for cyclists and kindly filled up our water containers at the nearest source.

A Kyrgyz breakfast in Kazarman. Our guest-house was really awesome and an absolute relieve after days of dust and vibrations.

Cédric once told me that it never rains in Kyrgyzstan. The poncho was reopened again for the first time since April (Barlow in the Australian Alps)

A fun-sized roadblock. Children stop us on our route on almost a daily basis to check out the bike, give waves, and scream hello. Cedric usually has to shake hands with every single male of the village (not matter what age or size)

The next morning, after entertaining some kids while we packed up, Cédric and I set off for the Kaldaman Pass, just 20km away but 1000m higher. Throughout the morning, we took breaks to see the mountainous landscape evolve around us. Unlike the day before, when all the mountains were shrouded in rain clouds, we could see far into the valleys and where we cycled from. Around 1pm, after a final push to the top, we were able to make a slow descent down into the Fergana valley. Once again, the landscape changed drastically, with the hills becoming dry and autumnal, and the first forests in weeks. We found a campsite next to a river and were greeted by a local man who kindly showed up where to find a hidden water spring. He also offered (via gesture) to have us camp next to his house, but we couldn’t be bothered to drag our bike uphill.

Encouraged by tales of smooth pavement down the road, Cédric and I set off on the last few kilometers of this rough track. Although dirt tracks never bothered us before, this 400km stretch brought us to our limits. For Cédric, it reminded him of his few weeks riding through sand and loose gravel in Zimbabwe (with a lot more elevation, but a better climate though, and approximately the same pace), where he could only inch along the road, happy to cover 40km in a day. For me, I was constantly annoyed by the sheer speed of the drivers going down these roads (which in turn, deteriorates the road even more) and their eagerness to wave, honk, and give a thumb’s up whenever they passed. Every time a car went by, it would kick up a huge cloud of dust for us to inhale while the people inside the car didn’t think too much about us besides having a picture of us on their phone. Both locals and tourists alike were guilty of this, although tourists would more often understand my gestures for ‘slowww downnn!’ A few kilometers from asphalt, a front spoke broke in the nipple and we were unable to repair it because we of course didn’t pack spoke nipples with us. Luckily, we ride on large sturdy rims and the front wheel could go on with one less spoke. Once we hit asphalt in the afternoon, Cédric and I glided into Jalal-Abad and found a guesthouse for the night. In the evening, we wandered around the local bazaar looking for spare spoke parts – this required using google translate, pictures, and asking multiple people where we could buy a bike wheel (a gross approximation, but it worked out in the end).

We basically went up all that mountain to be back at the same altitude on the other side – 90km of switch-backs, but only 20km away as the crow flies, and it took us 2 days.

Roadworks (or not, we are not quite sure what was going on in the center) in Jalal-Abad (there was definitely some asphalt – at some point)

The next morning, Cédric and I decided to forgo all sensible reason and cycle the 100 kilometers to Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second largest city. Now that we were in the Fergama Valley, all lush greenery had turned into dry, amber-colored grass and didn’t seem very inviting for a night camping. With the altitude now 2000m lower, the temperatures are also a lot higher. We made our way along the busy two-lane highway, using our mirrors often because of erratic Kyrgyz driving. I liken it to those YouTube videos of Russian dashboard cameras, where you watch and think, ‘No… they’re not going to do that, they’re not going to do that, OMG they just did it!’ The road (highway) was sporadically painted with white lines, which seemed like were more of a suggestion than rule. Every chance they got, Kyrgyz drivers would pass the slower car and the road would sometimes turn into three lanes instead of two. With the mirror, the noisy engines and a large unpaved shoulder, we could manage the 6h ride, but happy to know that the road to Tajikistan and in the Pamirs is a lot quieter. Late in the day, exhausted, we cycled into Osh and found some respite at our guesthouse.

]]>

After a night of inadequate hostel sleep (thank you group-travelers…), Cédric and I loaded up the bike and set off for Song Kul lake. From what we gathered from the hostel talk, visiting this lake is on many guide books’ top things to do in Kyrgyzstan. For us, not having much of a plan, the Song Kul was on our route towards Osh, so we decided to check it out, although the traverse implied two mountain passes at over 3000m. As we were leaving Kochkor, we stocked up on three days’ worth of food (including three cans of the worst quality of sardines imaginable) and some medicine for my horse allergies. Shortly outside of the city, the asphalt became gloriously smooth once again and we began the slow climb going south. Coming from the arid landscapes of Issyk-Kul, the views along this route took another dramatic change and became copper canyons. After lunch at a small restaurant, we said goodbye to good roads and turned west on a gravel road that would bring us towards Song Kul. In the late afternoon, Cédric and I found a flat spot that was suitable for camping: far enough from the dirt road and the dust of cars, and close enough to a river to drink and for washing-off that same car’s dust of the day. In the evening, as we were ‘enjoying’ our first meal of ketchup, pasta, and sardines, we watched the men from the nearby farm shepherd horses up to a yurt several hundred yards/meters up the mountain.

Leaving the hostel in the morning. It doesn’t look like it, but the inside was actually pretty nice!

Drinking 3L of Cédric’s random drink choice: malta, a non-alcoholic beer-like soda. Nice one, Cédric. Main reason of choice: the largest bottle in the shop! It actually somehow tastes better when warm after a full day in the sun.

Cédric, angered at all of the people zooming by us at top speeds, lined the road with rocks to make them slow down. Just a funny surprise for speed-racing vans… Also, notice the lovely washboarding (i.e. a complete nightmare to ride).

The next morning, we awoke to clear blue skies and set off to tackle what would be our highest pass on the trip for the next few weeks: 3450 meters. The day’s ascent began at 2400 meters of altitude, with only 15 kilometers to clear the pass. Going up took us the better part of the morning for many reasons: 1. the gravel road was steep and loose at some points, requiring us to push and 2. we met or passed by 8 cyclists on our way up – about as many as the previous 3 months. Whenever we crossed paths with other cyclists, a good 15 or 20 minutes was spent swapping stories and sharing route details – informing the others about which road to take and notes about good camping spots. Finally, around 1pm, we reached the pass and our joy was shared with a tour group of 20 Slovenians (with one who thoughtfully offered to take pictures of us with our own camera). We spent another hour descending into the Song Kul plateau before stopping on the side of the road for lunch. It was here that we noticed that something was amiss with our rear wheel axle as we were packing (something wasn’t tight), but just tightened the screws and slowly went down the road to look for a spot to camp for the night. Song Kul was much larger than we imagined (about 29 km at its widest) and circumnavigating the lake seemed endless. Although it looks like a large plateau, the dirt road is rarely flat, full of rocks and loose gravel, and we were struggling over the tens of kilometers of washboard (thanks again to speeding cars and buses, like if the dust wasn’t enough), so the speed wasn’t much faster than going up the pass. We also considered camping on the edge of the lake, but that dream died once our GPS told us that the lake was still over 2 km from the road. In the evening, we were greeted by passing herds of horses, all watching us suspiciously as they strode by.

A familiar phenomenon when we go over passes. Cassie escaped them right on time, leaving Cedric dealing with all questions/selfies/Pino-Q&A (that group from Slovenia wasn’t so bad actually)

Our camp for the night (target a river for water, and put your tent wherever you want in Kyrgyzstan!)

Waking up in the cool morning at 3000 meters, we ate breakfast inside our tent as we waited for the sun to warm up the area. With a slight breeze, we rode off in the direction of the Moldo Ashuu Pass, passing by yurt settlements as we continued. These yurts were sometimes used for tourist accommodations and others were inhabited by shepherd families, who went up into the mountains for the summer season to manage horses, cows, and sheep. Just as the day before, we slowly cycled towards the pass and were greeted by new scenery and landscapes. If you are not sure to be at the pass, just look at the road in Central Asia – it seems like the tradition is to drink a bottle of vodka and smash the glass on the ground if your Lada has made it up to the top! So second pass at 3250m reached at noon. From now on, 45km and 1800m of descent. It would sound easy and exciting if we were anywhere else or on a lightweight full-suspension bike (and probably would take less than an hour…), but we finished the descent at 5pm, exhausted from steering the 220kg down the road, alternating between washboard, large loose rocks and trying to not damage anything else on the bicycle. We finished the day camping near the Naryn river together with Simon and Steffi, two German cyclists that we had caught up on the first 3400m pass the day before. Here, as Cédric was tightening the bike’s screws from all the rattling and rocking, he found that the screw of the rear axle had sheared off at some point. The axle is a pretty critical piece since it’s what keeps both the trailer and the wheel attached to the Hase Pino. After some deliberating, we decided to zip-tie the trailer arm to the tandem’s stays and hope for the best as we continued our way to Osh, where there’s the closest bike shops and repair guys (still over 400km of dirt path away!). If anyone’s counting, we’re currently 1/4 for being able to repair/replace in situ the things that we broke on the bike (1. the tire/tube (√) 2. The handle bar 3. The kickstand screw and now 4. The axle screw). Of all the replacement parts we’re carrying with us, most of it seems like unnecessary weight at this point, and it is obviously the unplanned that is happening!

This way was probably more fun going down than up (well, we went up on something similar the day before)

Thinking about a camping spot for the night. Notice the asphalt – lots of dreams and hopes in it – maybe some Chinese workers did it and nobody had told us about it? – No, false alert… it only lasted two kilometers.

The next morning, we bid adieu to Simon and Steffi and started the long journey towards the Kara Koo pass. We hoped to somehow ride over the pass in the late afternoon, but the journey to the foot of the climb seemed never-ending. For the first part of the day, we were plagued with loose gravel and slogged along at max. 10 kilometers/hour down the road- to relieve the misery, we tried to focus on the surrounding landscapes instead of our depressing pace. Since it looked like it was going to take more days to get to Kazarman, we stopped in the last possible village and bought some more supplies for the trip. After a lunch in the shade 30km down the road, Cédric and I finally made it to the base of the pass at 2800m, and started the slow 1200 meter ascent – and the gravel road didn’t make it any easier. Around 5pm, we finally made it to the top, and some kids shouted at us, offering tea in the nearby yurt. We unfortunately didn’t accept the offer because we wanted to find a water source to camp next to before nightfall. A slow decent down a few kilometers, we found the first plausible water source – a well – and decided that this place was as good as any. As luck would have it, this area was also preferred by herds of sheep and horses that roamed the area, so our night wasn’t particularly quiet since we had to share the water spot with all the farm animals of the upper valley. The proximity to the road didn’t help either, as the water source is apparently also the place to (try to) repair the car that is unlikely to make it across the pass.

These 12% signs are everywhere in Central Asia, but it’s not really an indication of the real incline/decline. If it’s steep and uphill, it’s 12% up, if it’s steep and downhill, it’s 12% downhill! Sign standardization!

Looking over the valley of the Naryn river (Cedric’s dad somehow managed to call at that spot – no idea how we had enough cell coverage there!)

When we awoke the next morning, after a night of crappy sleep (thanks to animals and cars), our eyes were set on a guesthouse in Kazarman for our resting place that night. However, 75 kilometers of crappy gravel roads (and numerous hills) were between us and our goal. We continued our slow descent from the Kara Koo pass only to be greeted with a few smaller passes throughout the day. Along the way, we met a few cyclists and traded stories about the stretches that we just covered, everyone on a bike is aware that these several hundreds of kilometers are rough and not a pleasant ride. After our final descent (still lucky to top 10 km/h downhill on the gravel roads, that’s still twice faster than the ascent…) to the Kazarman valley, we still had a flat 17 kilometers to cover before we reached the city. We somehow had hopes that the road in the valley being flat, and used by farmers, it would be in a better condition. But here again, we were weaving back and forth on the road, looking for the smoothest track, and finally riding in some not-too-soft sand (although sand is a bit of a nightmare on a tandem become of the pressure on the tires) on the very edge of the road. In the late afternoon, windswept and dusty, we rolled into Kazarman and found a guesthouse to stay for the next two nights. Guide books mention Kazarman as a bit of a rough desolate place, separated from the rest of the country 8 months per year (there are mountain passes at over 2800m in every direction, and the passes are closed because of snow from the beginning of October to May…). Nothing to do: that’s a perfect spot for a rest day!

]]>