In Khorog, we treated ourselves to another rest day. We figured that the never-ending 130-kilometer ride ‘downhill’ warranted a day for our bodies to recover. Already, it felt like our time up high in the Pamirs was a part of a dream; in Khorog, the weather was warm and sunny with a soft breeze, there were people and decent cell service. ‘How did we manage to cover what we did in just 5 days?,’ I wondered. When Cédric and I gathered enough motivation to leave our hotel, we wandered to the local bazaar to buy some odds and ends: a hex key of a specific size and shape, hair ties (over 8 months, we lost the 5 that we had), and snacks. Already, we could sense the harvest season since there were boxes and boxes of grapes, watermelons and other produce filling the market – a lot more vitamins than the rice, potatoes and bread that composed our meals the previous week. After we wandered around Khorog’s short downtown and adjoining park, we spent the rest of the day writing blog posts (what we do on days off) and uploading pictures. In addition to being loved by cyclists, our hotel also seemed to attract a revolving group of politicians, looking more like Mafiosi than locals, surrounded by politicians-to-be and other military-personal with shiny decorations on the shoulders and jackets. They trickled in and out of the hotel gates at all hours, making apparently serious-sounding calls to other officials – it was funny to see the juxtaposition of these two types of clientele.

The next morning, after a hearty breakfast, Cédric and I set continued on the M41 which would lead us to Dushanbe. Immediately after leaving the city, we reached the Panj River which defines the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. For us, we felt like some sort of explorers seeing a forbidden land – Afghanistan was just a few hundred meters from us at most, a stone-throw away usually, but we knew that given the current political circumstances, we would never reach the other side. Instead, the river valley gave us the unique perspective of watching daily Afghan life unfold while perched on the Tajik side of the river.

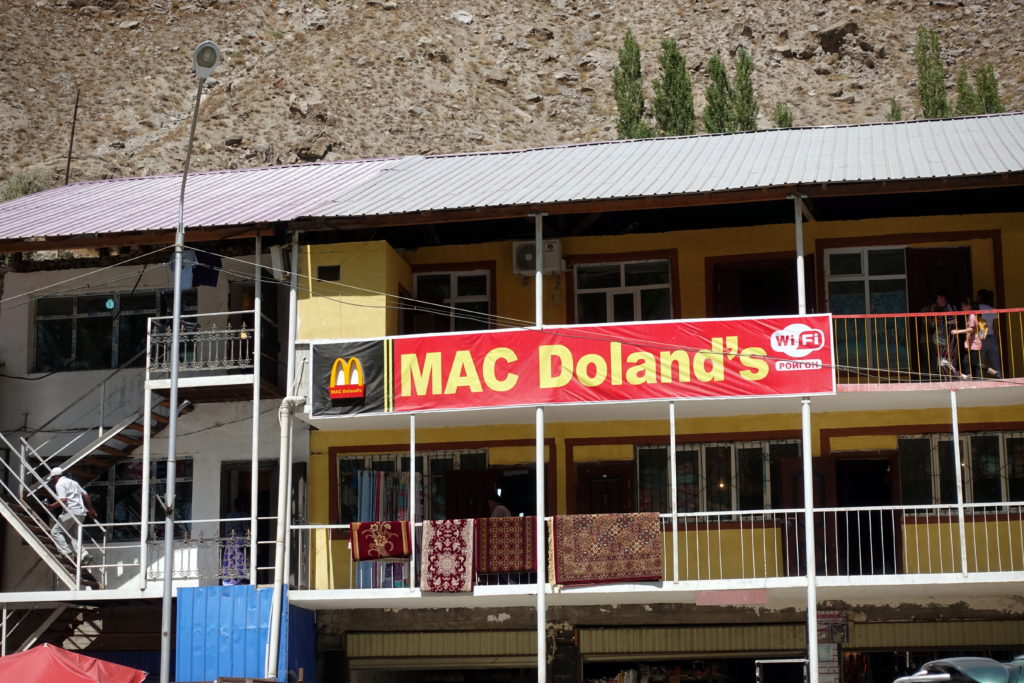

Apart from the bigger towns and villages, cycling through Tajikistan (and parts of Kyrgyzstan) gave us the feeling of seeing some vestiges of our grandparents’ childhood – nearly every house had its own garden that was neatly maintained (but not meticulously weeded), fruit trees abundant, and non-existing chemicals or other modern-agriculture-productivism-inventions. Indoor plumbing was still a luxury, so people got water from nearby wells or streams, multiple canals guided clean water from the mountains to the gardens, houses were constructed by the families, and kids were out in groups running around or racing us with their bikes, if they had one. Of course, it would be disingenuous to ignore the facets of modern life in the valley with it’s spotty internet service, SUVs passing us on the road, and access to refrigerated Coke in every village (or in some strange circumstances, RC Cola). Looking over to Afghanistan, on the other hand, gave us the feeling of what life could have been like again a few generations before. On the Afghan side, houses were more basic and some were still mud brick and walls (in Tajikistan, it was mostly cut stone and cement), access to an electrical grid appeared to be sparse and if any, supplied from Tajikistan, and roads were used mostly for foot and animal traffic (with the occasional car or motorcycle in the parts were large enough). On both sides, though, all the manual labor was completed without the aid of a machine.

On our ride out of Khorog, Cédric started complaining of stomach issues, so we got him a bottle of soda and sat at a bus station while we rested and had lunch. After sitting there for a few minutes, we were approached by an older guy who essentially wouldn’t accept that we were eating bread and snacks at a bus stop and told us to eat at his house. Because we passed up two opportunities to spend time with the locals on our way down to Khorog (we were offered to stop for tea when our axle broke and again when we had stopped for lunch that day), I was eager to take him up on the offer. I told Cédric, reassuringly, it’s just tea. It wasn’t just tea, however. We were invited to have soup (potato and sinewy meat) and other treats. The problem was that Cedric could not really eat anything too solid, and it is considered impolite to not eat what you are given in Tajikistan (and we have about zero vocabulary to explain that I am about to repaint the tiles), so eating the meat, the bread, the chocolates, the cookies, the fruits and vegetables, the soup, more bread, more soup… became a real struggle. Luckily, some “Keep Calm and Carry On” deep-breaths and sang-froid made him avoid a drama.

We sat with the family for a few hours, trying to tell them about our lives back in Germany (we’ve taken up the more relatable professions of teacher and mechanic) and explaining how their house and adjoining garden would run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars back in Germany, but when we have time we also try to explain that everything is a lot more expensive, and that although higher wages, getting an accommodation or even a car is very pricey. If we don’t have time or simply figure that the people are not going to understand (or look suspicious), we just pretend to not understand their questions. Our bicycle for example (frequent question), costs between “two bicycles” (cause it’s a tandem), “I built it myself” or maximum a fourth of what the car of the person might cost (still maximum 3 digits… which people already find way overpriced for a bicycle, it’s either for poor old people or a toy for children here – we won’t detail how much just the Rohloff costs).

People are always curious to know how much money we make and how much things cost where we live. We have to arrange the figures a little, being in Tajikistan makes you realize how lucky we are living in rich Western countries. As we parted, some of the daughters gave us bread and a kilo of tomatoes for our journey: we at one point explained how tomatoes don’t grow well in Germany, and that only carrots and potatoes grow there – sorry for our poor Google-translate Tajik vocabulary… They seemed amazed that we could not grow all those fruits and vegetables in our garden. We continued down the road in the afternoon to a guesthouse in Rushan, where we had dinner with four other cyclists heading the opposite direction.

The next day, we continued down the Panj Valley, slowly making our way down the road. Although much of the road was asphalted, potholes and stretches with gravel were abundant. Our speed was slow, and the rough bumps didn’t help Cédric’s stomach-ache. Around noon, we found a tree to sit under for lunch and Cédric took a long nap to ease his pain. When we finally decided that it was time to go, we only made it a few kilometers down the road before the first plausible overnight stop appeared. Because Cédric was unwell, I asked around for a homestay and someone offered to open up their doors to us. We spent the rest of the afternoon resting and decided to cook our own dinner for the night. The house owner, eager to make his guests feel comfortable and welcome, was ever-present and just slightly annoying. Seeing that Cédric was unwell, our host took him to the hills and climb on a cliff to look for a bitter herb cleaned in the river to soothe his stomach, exclaiming along the way, “Pamirski medicine!”. Really bad taste for sure, not sure about the effectivity, although the stomach pains did not get worse… Another time, while we were eating, he gave us home-dried apricots and cried out, “Pamirski snickers.” It turned out that everything we were given would be supposed to be good for Cédric’s stomach.

Seeing that Cédric was feeling a bit more fit the next day, we cycled off and continued down the Panj River valley. The valley remained narrow and jagged mountains enveloped both sides – and small gatherings of houses sprouted up when there was an adequate water source and flat land. Sometimes, the road was fit tightly between the rock face and the river, with no room for error when driving. Much like the previous days, we were slow due to navigating around deviations in the road. In the afternoon, just as we were thinking about asking around for a place to camp, a man pulled up next to us and without hesitation told us that we could eat and sleep at his place. After checking to make sure he didn’t live 20 kilometers down the road, we jumped on the bike and followed him home. Once we got to his home and parked the bike, it immediately became apparent that this guy, while very generous, was also piss drunk. After trying to chat with him for 10 minutes (which was mostly him repeating everything about 5 times), he excused himself to take ‘a short nap’ for the Vodka to dissolve in the veins (we didn’t see him again until morning). For the rest of the evening, we were served garden snacks (Pamirski snickers, dried mulberries, grapes, apples, figs, peaches… etc) and had dinner with the neighbor boy and the man’s son. We also slept outside on the tapchan (a raised table that often serves as a bed in the warm months).

We awoke early the next morning with the sun (I guess it’s a benefit of sleeping outside on a table) and had breakfast with the now hungover man. As we were eating our soup, he explained the he needed to rush off because he was a teacher at the local school. Go figure. We left soon after and thanked the son and daughter-in-law for graciously hosting us while their father was incapacitated. From what we understood, we weren’t the first cyclists that he picked up on his way back from the bar. The day’s ride was more of the same as the last few days, but now Cédric was feeling better. We slowly progressed, stopping to chat with the cyclists and foreigners that we met along the way. When we stopped on the outskirts of a village for lunch, a local man came and picked a few ripe, white peaches for us to have with our bread and Pamirski snickers. In the afternoon, when we stopped in a village to inquire about a camp spot (suggested by the cyclists we had just passed), a group of kids led us to a clearing in a tree grove nearby. As we unpacked and setup camp, a revolving number of village kids came to watch us do our evening routine. However, what was different with these kids is that they never got bored watching us. Up until nightfall, at least four kids sat outside our tent and watched Cédric and I rest inside. We attempted to seem as boring as possible to get them to go away, but to no avail.

We set off early the next morning, happily child-free, towards Qalai Khum in hopes of better roads. From what we heard for other cyclists, some good pavement is supposed to appear somewhere around there. As we tackled our last few undulating hills, we were able to reach the town by midday and decided to join a large group of men eating lunch outside of a restaurant (the only woman in the area was the one serving up the dishes). Cédric was finally feeling well enough to give plov (and meat) another go, so we ordered two generous helpings. We hung around Qalai Khum for another hour after lunch to get a few groceries, drink a coke, and respond to all the passing kids’ questions (Hello! How are you? What is your name?) One girl even ventured to try something different and asked, after a little hesitation, ‘Selfie?’ We obliged.

Leaving Qalai Khum, cyclists have two options in reaching Dushanbe: opting for the shorter, unpaved, and more strenuous northern route, or the southern route which is paved, but longer and has more traffic – both routes have the same elevation gain. Cédric and I had asked nearly all of the cyclists what they suggested and figured that the southern route would be less axle-breaking even if we had to cycle and additional 100 kilometers. In the afternoon, we continued cycling out of Qalai Khum and along the Afghan border. To our dismay, the wonderful asphalt that we were promised didn’t start until where we stopped for the night in Yoged, 30 kilometers after the city.

Bobby

September 16, 2018 — 11:16

I like hearing about your interactions with the locals, but tomatoes don’t grow in Germany? Quatsch!

I think my mom is your biggest fan 🙂

Cassie & Cédric

September 16, 2018 — 11:43

Greenhouses and Italian imports don’t count! And the two kilos of green tiny tomatoes that Helmut manages to get in his Schrebergarten don’t count either 🙂

Yes, Ruth has an impressive answer rate and speed! It’s always nice to read her comments 😉

Hel-loh Bluth

September 16, 2018 — 21:03

Annyong!

Cassie & Cédric

September 17, 2018 — 03:30

Annyong! Annyong, annyong !

Ruth Viens

September 17, 2018 — 01:56

Love reading about your interactions with the locals and how inviting they are.How very lucky we all are! So glad you are feeling better Cedric. Be well and safe! Ruth

Cassie & Cédric

September 17, 2018 — 03:32

Well, it’s supposedly impossible to cross the Pamirs without getting sick…we didn’t escape it! Luckily we both didn’t get anything serious, and could still continue every day.

Josette Koets

September 21, 2018 — 01:48

Drinking all of that Coke reminded me of when I was a little girl; when Colby or I had a stomach issue, my Mom would give us teaspoons of Coca-Cola syrup that was available at the pharmacy…..no longer, though. My very favorite photo is the selfie with the girls….I love it! As for tomatoes, we’re processing bushels of them in various forms. Thought of Cassie when she was here helping me with sun-dried tomatoes (which I’ll never do again, thanks to all of the fly larva that hatched in the containers that winter, lol. Dehydrator only!). Anyway, enjoy all of that fresh produce! Love, Aunt Jo

Cassie & Cédric

October 3, 2018 — 05:37

Seriously, coke is amazing for digestive issues. That should be covered by the health insurances (okay, only for people burning enough calories though!).

Colby & Carol

October 10, 2018 — 02:31

‘Hello’ again!

Coca-cola – the cure all. Good for removing paint too!

Great memories – our mother giving Josette and I teaspoon of Coca-cola syrup for upset stomach issues (I think I may have faked it longer, on atleast one occasion, as I found the taste to be much more pleasant than any other medicine (Josette, fess up, did you ever take the ‘medicine’ syrup bottle out of the bathroom closet and take a hit of it?).

Very nice people to invite strangers in for the night. Curious kids, and I’m sure you were talked about in their schools the next day. Would have been great to have brought along a box of business card type momentos, with a picture of the Hase Pino and BOB on them, to give to the kids – the stories that would be told . . . and some may aspire to have their very own Hase cycle some day!

Love, Colby